Watch over 100 videos in my playthrough of BioShock: The Collection

After years of avoiding spoilers, I started playing BioShock Infinite a month ago. I wrote my first impressions after reaching Battleship Bay. Now I’ve finished the game, I’ll share my final thoughts:

BioShock Infinite is a visually beautiful video game with some fun moments, overshadowed by crappy game design, a skeevy protagonist, and a muddled mess of a plot, that demeans women and trivializes racism.

I loved BioShock and BioShock 2, and I wanted to love Infinite, but it just didn’t work for me.

I played Burial at Sea, but this article addresses Infinite because a game should stand on its own merit and not need an expansion to fix or explain its failings. I will talk about Burial at Sea at the end.

* * *

WARNING: MAJOR PLOT SPOILERS

* * *

Crappy game design

Shooting dominates Infinite, when you’re not busy looting garbage cans for money, cash registers for cotton candy, and robots for oranges. Sure, there’s shooting in BioShock and Fallout 4, even in Dishonored, and those are games I enjoyed. So what’s the difference?

In BioShock, enemies are monsters, spliced, twisted, barely human, and beyond redemption or cure. Killing them is a piece of mercy. But, in Infinite, enemies are human. An argument could be made that white supremacists are barely human monsters beyond redemption, too, but I also had to shoot the Vox Populi, an army of Columbia’s oppressed. Despite the best efforts of the game to make them out to be as evil as their oppressors, all of that killing just felt wrong.

And boring.

In Fallout 4, there are also towns to rebuild, characters to befriend or romance, an open world to explore, crops to plant, junk to scavenge and sell, people to rescue, factions to join, armor to upgrade, unique weapons to find, recipes to cook, and more.

In Dishonored, I have the option of stealth to avoid conflict or I can choke enemies with a non-lethal takedown. There are no non-lethal options in Infinite, and no stealth, except for the asylum level near the end of the game, with a whopping total of two Boys of Silence I could dart past.

All right, those are just different games all together. What about other BioShock games?

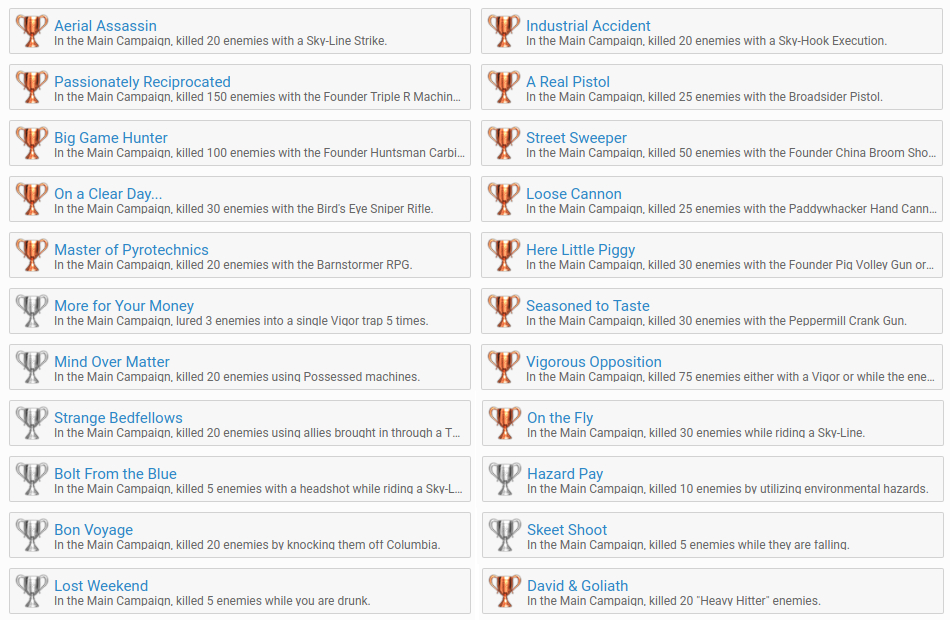

I felt as if I killed ten times as many people in Columbia as all the splicers in Rapture, between Bioshock and BioShock 2 combined. And I probably did, considering how many BioShock Infinite trophies are based on killing people.

To get all the achievements in BioShock, ten people are required to die. In Infinite, hundreds. Most of the trophies in BioShock are based on using the research camera, hacking, inventing, upgrading, and collecting. Infinite features no research, inventing nor actual hacking, at all.

The game’s constant reminder, “remember to use your vigors,” felt like a plaintive request rather than genuine assistance. I managed to get through most of Infinite with my machine gun and RPG, or playing “shooting gallery” with a conveniently-placed sniper rifle.

In Infinite, vigors are required for powering one gondola and unlocking a few areas for extra loot. Whereas plasmids are integral to the level design and to the player’s survival in previous BioShock games: Door controls zapped with Electro-Bolt; frozen areas thawed with Incinerate; dark corners explored with Scout; hidden goodies grabbed with Telekinesis; cameras and turrets tricked with Security Command; or enemies flushed out of hiding by bee swarms.

In the very last battle of Infinite, I did use Shock Jockey to keep the Vox away from the airship’s power core, but let’s stop right there for a minute to ask: Why could Elizabeth conjure walls on either side of the power core to protect Booker, but somehow couldn’t conjure walls to protect the damn core itself?

Infinite is inconsistent, incoherent, contrived and chaotic. Elizabeth, voxophones and loudspeakers often talk over each other, so none can be understood, and it’s all so muddled even the captions can’t sort it out. Possession turns some turrets friendly forever, while others are only friendly for a few seconds. Tantalizing coins shimmer behind invisible walls and can’t be collected. A ghost suffers critical damage from headshots but can’t actually be killed, and despite floating everywhere somehow leaves footprints for me to follow.

The PS4 square button drove me crazy. I frequently found myself going through a dead man’s pockets instead of reloading, or reloading instead of catching a health kit from Elizabeth. This is even worse during the final battle when, on top of everything else, square controls Songbird.

The tears — or as I call them, the singing space-time vajayjays — are described by Elizabeth as a form of “wish fulfillment,” yet she doesn’t wish for anything more than hooks, sniper rifles, water puddles and the odd motorized patriot. All her bragging about the books she’s read, and that’s the best she can do?

The excuse given for her limited ability is a siphon machine that somehow prevents her from using her powers to the fullest, at least until the plot calls for her to take Booker into an alternate timeline, pick a rose in an elevator, or summon a tornado. I’m reminded of the mechanics of space travel in science fiction: “At the speed of plot.” That’s how tears work, as well.

I overlooked the fact that every dismount from the skyline should have broken Booker’s legs, because the skyhook is a fun feature of the game. “The rule of cool” and all that. In a similar way, I may have overlooked the chaotic soundscape, repetitive boss fights, constant backtracking through levels, Booker’s inane dumpster diving, the two-weapon limit, the square button, and other irritations of this game, had I liked the characters and the story. But, I didn’t, and that’s the REAL problem I have with Infinite.

Skeevy protagonist

In BioShock and BioShock 2, the protagonists Jack and Delta are in a bad situation due to no fault of their own and have to fight for survival. In Infinite, Booker DeWitt is a killer, a human trafficker and a douche. He seems, at first, to be a rescuer, but then we discover he’s only accepted the job because he’s got gambling debts and he intends to take Elizabeth, against her will, to a place she doesn’t want to go, for money, and kill a shit ton of people doing it.

If that isn’t bad enough, by the end of the game we find out it’s much worse. He not only sold his own baby, he’s somehow Comstock himself, the violent racist prophet of Columbia.

Jack and Delta are silent protagonists. Giving Booker a voice added no value. Most of his lines are either insignificant, like “holy shit” and “thanks,” or game tutorials such as, “I need to take this skyline to Monument Island.” Better dialog might have made a better Booker, and may have moved me to care about the plot twist and his ultimate fate.

The only Booker line I liked showed up somewhere around the middle of the game. He says, “Sometimes there’s precious need of folks like Daisy Fitzroy… Cause of folks like me.” When I heard that, I thought, wow, that shows self-awareness and an awareness of what’s going on around him, and there’s a sense of morality in what he said. It made me hope that he would eventually develop a personality, and maybe even get with the Vox and fight the good fight.

But, no.

There are moral choices in the previous BioShock games — save or harvest the Little Sisters, spare or kill key characters — and those moments not only affect the outcome of the stories and the actions of other characters, they allow us to bond with the protagonists, to truly become the main character.

Infinite offers only three in-game choices — stone the interracial couple or not, kill or spare Slate, pick out a pendant for Elizabeth — and those choices have no impact whatsoever on the story, the ending, Booker, Elizabeth, or anything else. They did fuck-all to help me relate to Booker.

A muddled mess of a plot

In BioShock & BioShock 2, characters, environments, audio recordings, weapons, level design, all serve the story. But in Infinite… I can’t even figure out what the story is.

What did the salts and vigors have to do with anything? In BioShock, Rapture is a city with scientists and capitalists, unfettered by morality or regulation, who use sea slugs and little girls to produce and gather Adam and Eve, turn humans into Big Daddies, and create new abilities through gene splicing. How does that fit the milieu of Columbia, city of right-wing religious folks who dislike Darwin and the devil?

If Booker is Comstock, then why doesn’t anyone in Columbia recognize him? It’s not because of the age difference; there’s actually a voxophone that mentions Comstock suffers from rapid aging after being exposed to the Lutece Device. “Why does this Comstock decay, while a Comstock in another world remains fit?” So the young Booker should have been somewhat recognizable. Instead, citizens spot him by the “A.D.” brand on his hand, shown in the warning posters.

Why does Songbird have a connection to Elizabeth? If Songbird is trying to protect her, why does it keep tearing apart buildings and nearly killing her? And if Columbia has something that can rip apart the city, why can’t it defend them from the Vox uprising?

“Songbird, he always stops you,” Elizabeth says in 1984. But if the realities are “infinite,” why aren’t there any where Booker succeeds? “Constants and variables,” is the phrase repeated throughout the game, like a mantra. I guess it sounds better than “contrivances and plot devices.”

Who the hell were the Luteces? Delightful eccentrics? Whimsical villains? Annoying red herrings? Siblings? Lovers? Two alternate reality versions of the same person, but different genders? Then where’s the female Booker and male Elizabeth? Now, THAT would have been interesting.

Then, after the credits roll, there’s that bit where Booker pushes open the bedroom door, calling to Anna. What did that mean? Had everything been a dream?

At the end of BioShock, I cried. At the end of BioShock 2, I cried even harder. At the end of Infinite, I laughed. You know who did a time-warp story brilliantly? Dishonored 2, in the mission “A Crack in the Slab.” But Infinite is a ridiculous mess.

Demeaning women

Elizabeth seems to be presented as a romantic interest, from her trope tower rescue, to her cleavage window, to her Princess Bride-like “I’ll go with you if you spare him” scene. I thought she might turn out to be some form of Booker’s dead wife.

But then we find out she is actually Booker’s daughter? Ewwww.

Elizabeth’s powerful abilities don’t make up for her blatant objectification. It is always Booker’s narrative, not hers. She serves his physical and emotional needs. She finds him health kits, ammo, money and salts. She is the motivation of his actions and his inner turmoil. She requires him to rescue her (again and again and again), and when he doesn’t, she becomes what Comstock (who is also Booker) wants her to be.

The developers give her amazing superpowers then contrive a plot in which she can’t use them to save herself. Nope, her fate depends on a gambling, child-selling asshole whose alter-ego is a white-supremacist wife-killer.

Her best moment, in my opinion, is when she whacks Booker with a wrench and escapes, after discovering that he lied about taking her to Paris. But her anger doesn’t last long, thanks to some dockworkers who assault her and rip her modest dress open at the bosom, driving her back to Booker. Better the devil you know, I guess.

A viewer told me that Elizabeth’s torn dress is meant to outrage the player, not titillate. Is the racism of Columbia not outrage enough? The attempted stoning of a black teen and her white boyfriend? The abject poverty of Shantytown? Elizabeth’s lifelong abuse, locked away from human contact, watched and studied without her knowledge or consent? Is all of that not cause enough for outrage? She must be sexually assaulted and exposed, in order to facilitate player engagement? Really?

If the torn dress is meant solely to elicit sympathy for Elizabeth, why does she change into a new outfit with even more exposure? Elizabeth’s version of Lady Comstock’s dress just happens to be missing the high-necked lace collar shown in all of Lady Comstock’s portraits.

I’ve also heard the “historically accurate” explanation of Elizabeth’s dress. No, there’s nothing accurate about wearing an uncovered corset. A corset is an undergarment, and it is indeed a corset, because it is labeled as such when Booker is prompted to lace it up for her in Comstock House.

I have nothing against cleavage or sex. Hell, I write adult fiction for fun and for money. But sexualizing an emotionally abused teen is super pervy and exposing boobs as shorthand for “she’s grown up now” is weak storytelling that reeks of sexploitation and fan service.

Speaking of Lady Comstock, in Victory Square there’s a conversation where Elizabeth suggests that Lady Comstock may be alive in an alternate reality where she never met Comstock. To which Lady Comstock’s ghost replies, “Or (in a world) where I saved him?” This really repulsed me because it implies that it’s somehow Lady Comstock’s responsibility to fix the violent and abusive man in her life. The very man who killed her.

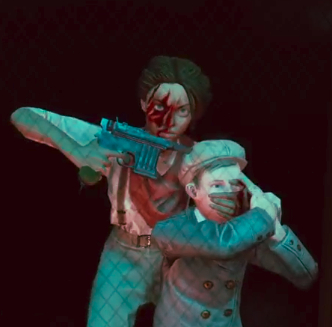

Then we have Daisy Fitzroy, falsely accused of murdering Lady Comstock. A woman of color dares to stand against oppression, and the developers chose to portray her as a vicious child-killer.

Trivializing racism

The game does an amazing job setting the stage for Columbia’s conflict by contrasting its Utopian idyll with its brutal bigotry. On the way to Monument Island, I found a secret society of progressives, printing pamphlets down the street from a temple to John Wilkes Booth. I spent an hour marveling at the sights and sounds of Main Street, before I found myself in the midst of a horrific raffle where I “won” the opportunity to stone an interracial couple.

But it isn’t long before Infinite declares it’s own political points moot, and racism is nothing more than set dressing. The game encourages us to just shoot everyone, they all deserve it.

“The only difference between Comstock and Fitzroy is how you spell the name,” says Booker, in the lift while leaving Shantytown.

“They’re just right for each other… Fitzroy and Comstock,” says Elizabeth in the Finkton factory. Then she says it again, in Port Prosperity, just in case you missed it. “Fitzroy’s no better than Comstock, was she?”

Infinite tells us, over and over, that there is an equivalency between jingoist, authoritarian white-supremacists, and the abused, impoverished, despised, exploited working class of Columbia. To say Comstock and Daisy Fitzroy suit each other, when one is hellbent on violent oppression and the other is fighting that oppression, is a bullshit conclusion to the game’s social and political setup.

I came away from Infinite with a sense that Ken Levine tried to make a great game but Infinite got crushed under the pressures of a big budget and triple-A executives who demanded the game appeal to a young white male demographic: Simplified shooter, dudebro protag, boobs, and negate the political themes.

I could be wrong, but then there’s …

Burial at Sea

The downloadable content (DLC) Burial at Sea seemed like an apology letter, acknowledging and addressing many of the gameplay and story problems I had with Infinite.

For example, there’s a weapon wheel, so the player can carry more than two weapons at a time. Medical kits can be carried and used as needed (something I complained about in my previous Infinite write up). There’s a significant stealth component and non-lethal options for neutralizing enemies. A great deal of time is spent explaining the connections between vigors and plasmids, Handymen and Big Daddies, Columbia and Rapture.

Elizabeth is the main character in Burial at Sea part two, and the storyline punishes Booker, acknowledging that he’s an asshole, though it later brings him back as a helpful voice in Elizabeth’s head and her “only friend,” underscoring her loneliness and her unhealthy relationship with this villain/parent. She becomes the likable if conflicted protagonist, with depth and personality, that I’d wanted all along.

Burial at Sea also attempts to change Daisy Fitzroy from a villain “no better than Comstock” to a self-sacrificing savior who voices serious doubts about the uprising and the resulting violence, and who never intended to kill the child at all but was only pretending, due to a request from the Luteces.

Helluva retcon.

~ J.L. Hilton

Connect, support, comment or contact the author here

Here’s a fun link: Dunkey sums up the BioShock Infinite experience